You have studied UX design, read books and blogs, taken workshops, and attended conferences. Your LinkedIn timeline is filled with content about UX processes, showing you what’s the ‘new’ way of doing UX design.

The pressure in the design world is tangible, and you must ensure you are better than a machine at design. AI is coming to steal your job.

But, if you want to find the proper way of doing UX - whatever that means - you better not google it; the internet is a jungle.

It seems that the only way to achieve great results as designers is to aspire to implement an outstanding design process. The pressure on processes is also evident during interviews when we are asked about it constantly.

What if we move away from processes and look at other factors to improve our design practice? Following the ‘correct’ process is not a symptom of a customer-centric business.

As part of the series, we first analyse what we mean by design processes, and then we explore the concept of design maturity and why it is vital for businesses; in the end, we uncover practical steps that we can take to create a customer-centric culture, and I share more about my experience.

Let’s start from the beginning, talking about the design process.

The Design Process: textbook

If you have wondered what process to use when doing UX, the answer is straightforward. All the processes you find in books and online are the same and are all based on User Centre Design (UCD). Debbie Levitt’s article explains it incredibly well by exploring (and mocking!) ten different processes.

This is a screenshot of Debbie’s article. It shows that it doesn’t take much to spin a new framework!

As long as you stick to a few main principles, the name doesn’t matter.

- Understand the problem to solve

- Create a solution

- Test it

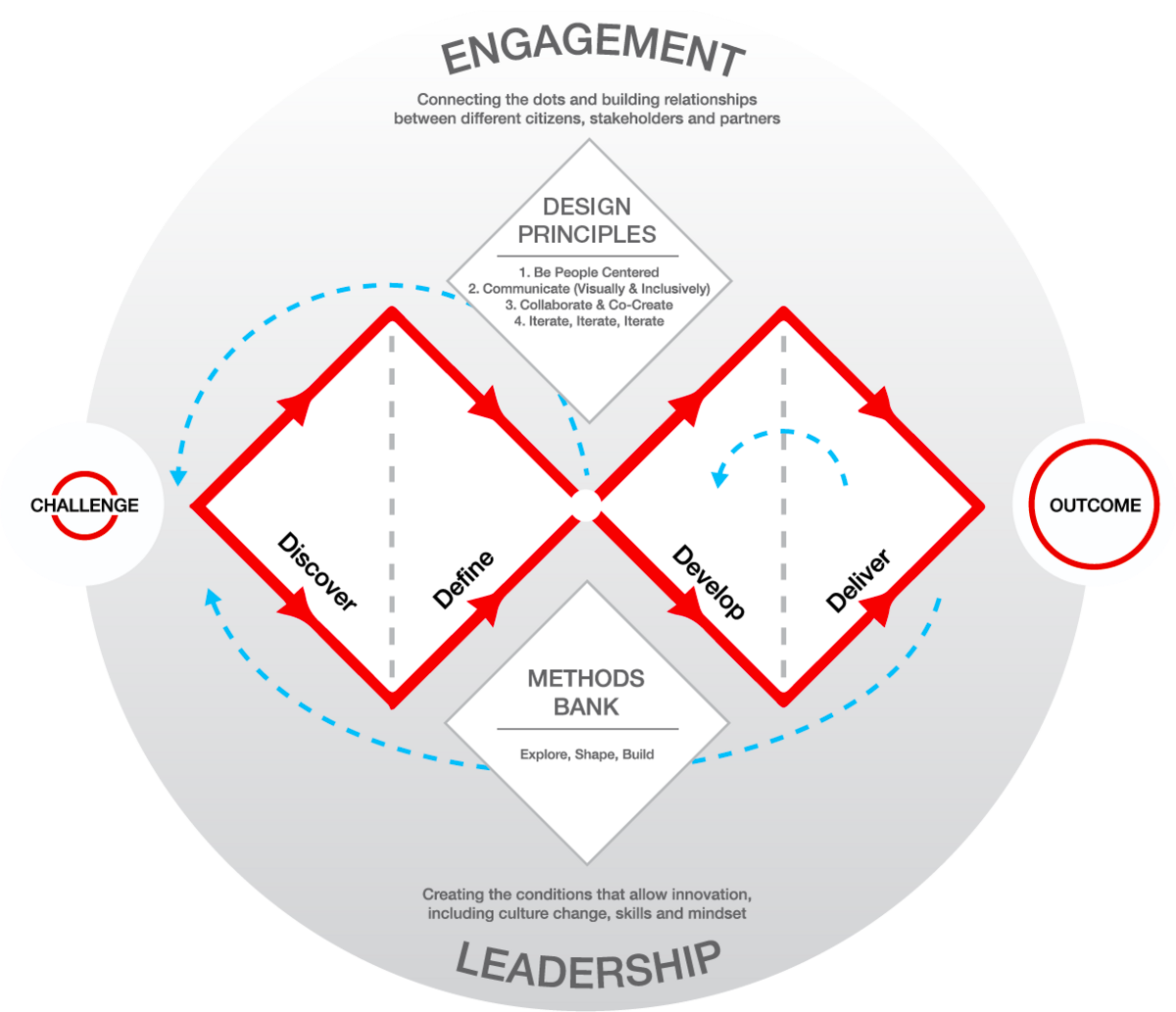

The most well-known design process is the Double Diamond, created by the Design Council. This is based on UCD, providing clear phases to take you from problem to solution.

Framework for Innovation by the Design Council

The fundamental of this process is like any UX process:

- Understand the problem. Your business might have an assumption or a real issue connected to a product or a service. You can delve further into the problem through user research.

- Define the problem. Once you have researched the problem, you can start defining it based on the insights gathered. This helps narrow down your problem area.

- Design the solution. It’s now time to design your solution and explore different ways that you can solve the problem.

- Test. When confident with a solution, you can gather further user insights by testing it. Then, you create more designs and test them until you have a solution that fits your user needs and helps the business achieve its goals.

The Design process: real world

I follow a process (sometimes) from The Design Institute

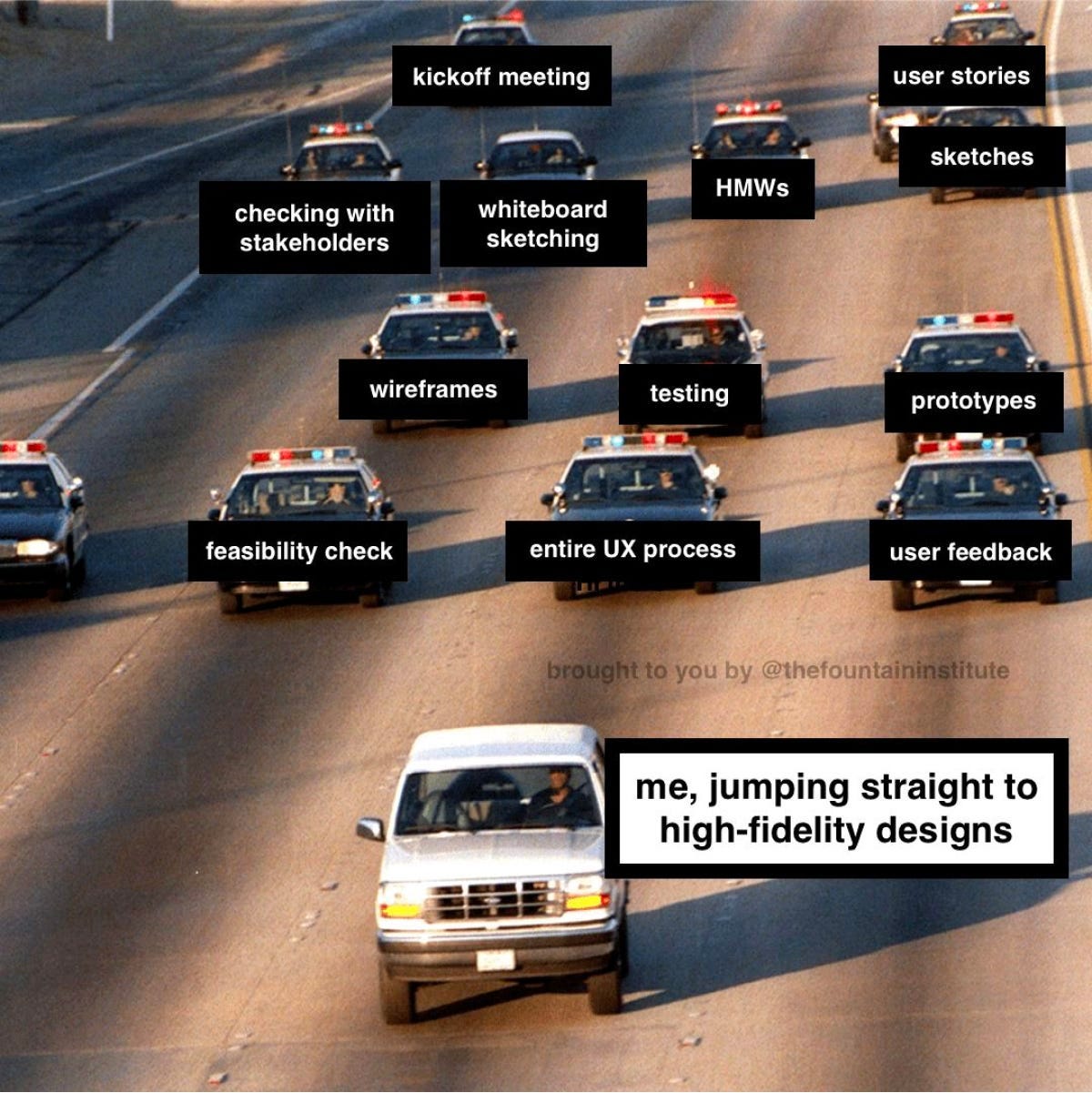

You are probably thinking that you do not always go through those steps. Sometimes, you are given a defined problem to solve and start designing immediately. On other projects, the time allowed for generative research is just a few days at the beginning of the sprint, so you only have the time to do basic desk research. You are not alone!

Many businesses do not have well-defined product development processes and do not understand the value that research and design can add to generate revenue, find product market fit, or whatever their goals are.

This generates low job satisfaction among designers, who are frustrated because they spend most of their time fighting for better processes or just get bored pushing pixels rather than contributing to understanding the problem and finding the right solution.

When we look at design processes, they feel like a utopia. We can’t get all those steps in place in our projects. The reality, though, is that we don’t really have to.

Applying a UCD approach will vary depending on the project and the business. Sometimes, the company already has tons of knowledge in a problem area, and you are working on contained scenarios. Therefore, you might decide that you do not need to run extensive research. Other times, you might work on an entirely new product and decide to run comprehensive research to understand more about the problem area.

As long as you keep close to your users, relying on internal knowledge, going straight to design or conducting extensive generative research are all great ways to design with UCD in mind.

Break the UX design process

So, if the design process isn’t always the same, it doesn’t matter, and it’s probably a good thing. Even if a good understanding of a design process is essential, you must use your critical thinking to evaluate the best process to get to the solution.

In his article, Ben Brewer provides many examples of moving the focus from sticking to a design process to having a series of tools that designers can use depending on the problem. He focuses on understanding the knowledge around a specific problem space and its associated risks. Based on these factors, designers can evaluate the best tools to use to get to an optimal solution. The more the risk, the more research is needed.

Scenario 1

Scenario 2

Scenario 3

With problems that are low risk and within your problem space, you can feel more confident in creating something straightaway and testing it out with users, gathering data and iterating on them.

With a design tool approach, you can be more flexible in identifying the best starting point for building a customer-centric culture in your organisation.

Customer centricity

Now that we are less focused on the process and more on solving problems in the best and most efficient way possible let’s look at the concept of design maturity as a basis to take the business towards a more customer-centric culture.

The NN/g group defines design maturity as the ‘[…]quality and consistency of research and design processes, resources, tools and operations, as well as the organisation's propensity to support and strengthen UX now and in the future through its leadership, workforce and culture.’

As you can see from this definition, the design process makes an appearance, but it’s not everything you need for a mature design practice. It’s about quality and consistency, as well as supporting and strengthening the value and role of UX.

Why are we talking about design maturity?

I think design maturity is crucial for teams just getting started and finding their feet in organisations that aren’t aware of what customer-centricity means for them. That’s the position I have found myself in quite a few times!

When we have a business that gets designs and its value, it allows teams to connect to their users and not just create screens. Designers who are closer to customers can help the business make a difference. So, if we elevate our design practice and mature, we can be more customer-centric. This article from Reforge articulates much better than I could do.

Why should we fight for customer centricity?

The answer is simple: to increase revenue, help businesses achieve their goals, and of course, fulfil user needs and goals.

Many companies achieve good results, close deals, and make money. This is what a business is set to perform. What if the business can achieve more? What if there’s a differentiator that can allow the company not just to have good results but extraordinary results? What if a business can change people's lives for good?

Customer centricity is the differentiator.

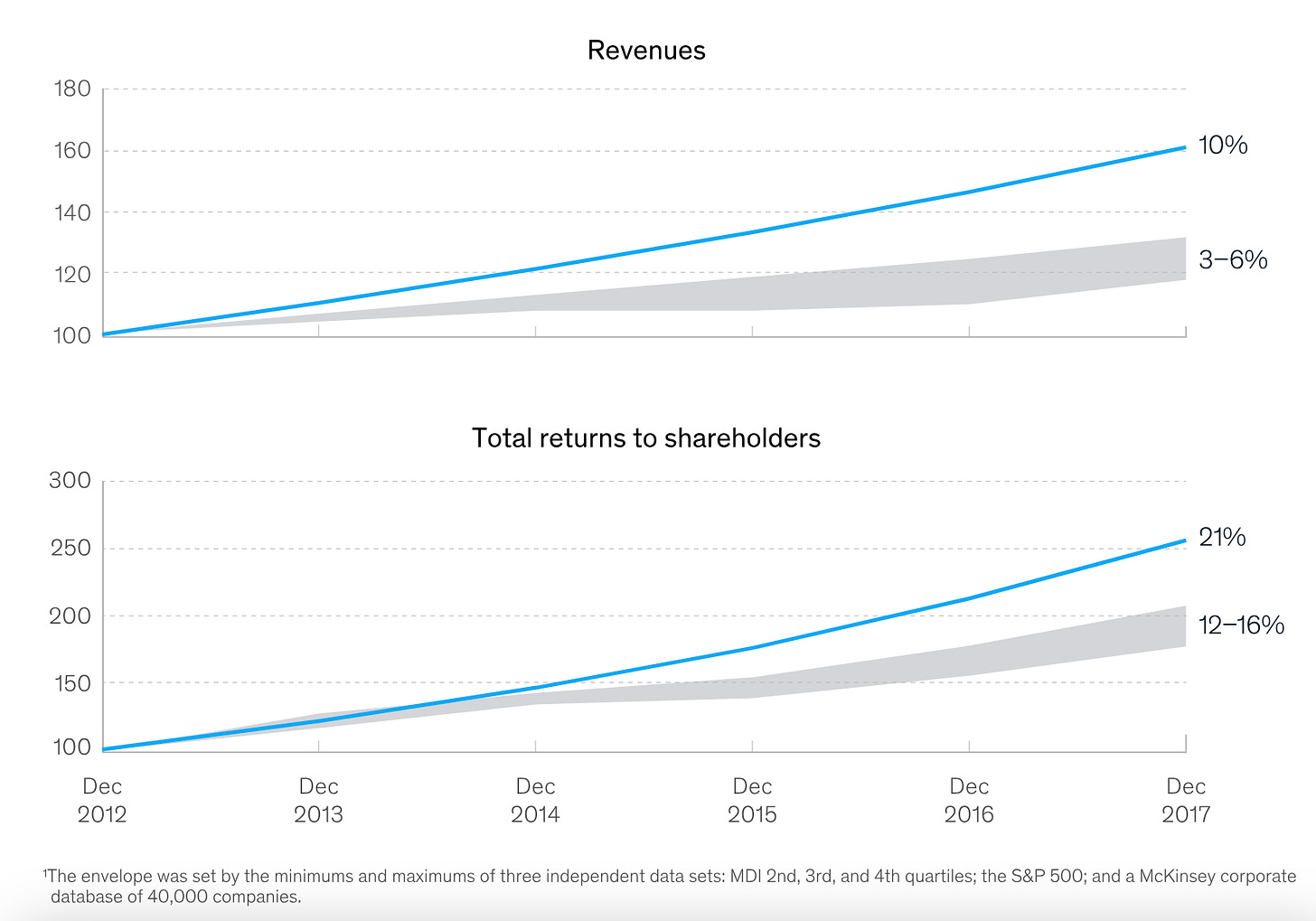

McKinsey wrote an extensive report in 2018 based on five years of research that analysed millions pieces of financial data and linked those to thousands of design actions. This led to the MDI (McKinsey Designer Index), which analyses the characteristics of businesses that show excellent design practices that contribute to creating business value.

The results showed that those companies with excellent customer centricity have far superior business performance, generating higher revenue and higher returns for their shareholders.

Customer centricity allows businesses to work closer to their customers, understand them further and identify needs, goals and pain points necessary to create products and services that people buy. Customer centricity can allow businesses to increase sales, improve customer satisfaction and reduce costs, generating exponential business value.

Starting from design maturity

When you work in a company that sees designs as a screen factory, the conversation about customer-centricity needs to start from a completely different level. Telling your manager, often in product, marketing, or technology, that designs can help with the revenue target might seem abstract and far from adding the icon to the screen they need now.

How do we engage managers and stakeholders?

I have found the conversation around design maturity very helpful in showing the business the steps to take to customer-centricity.

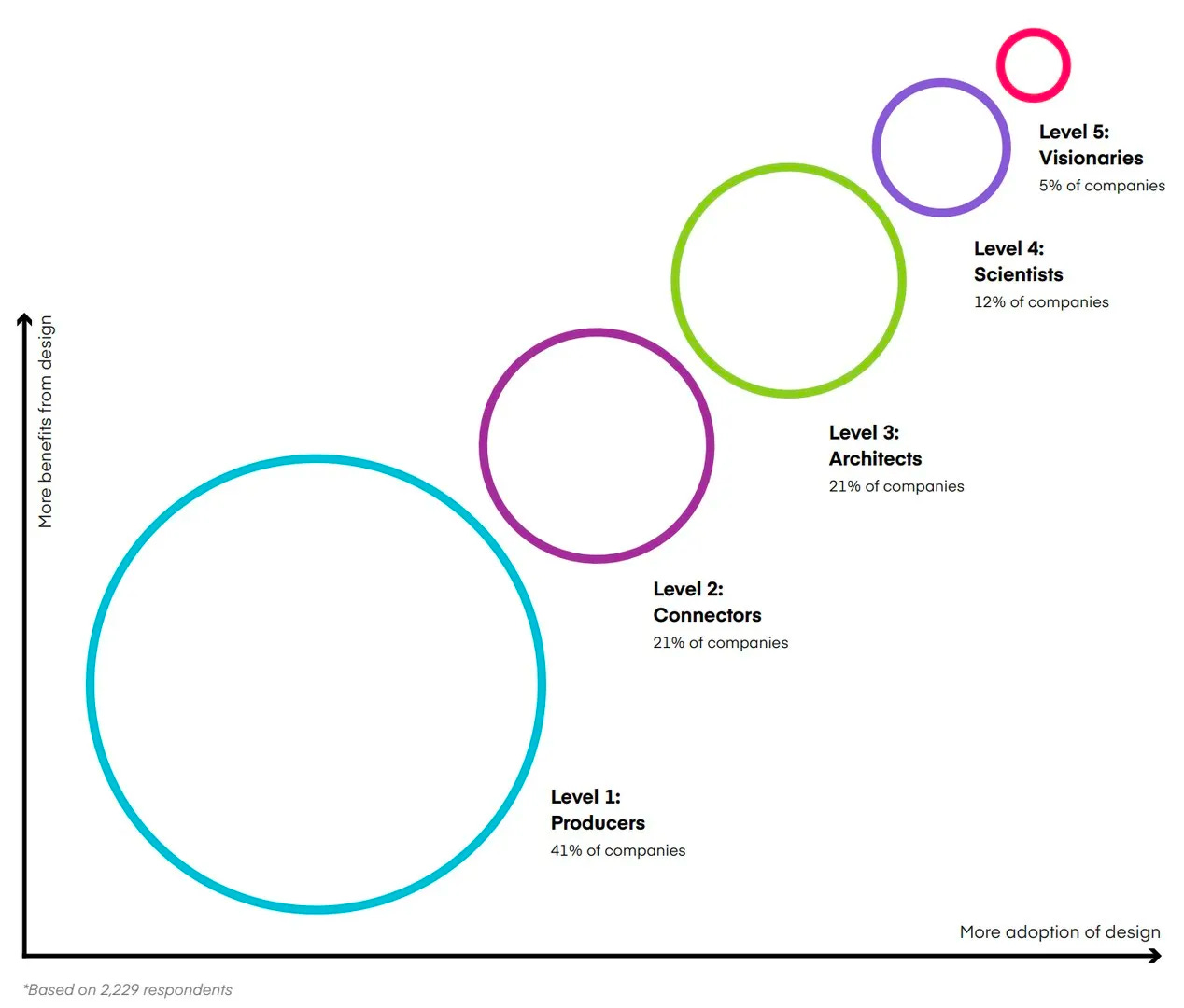

InVision has created a categorisation to identify companies’ design maturity, which shows how you can strengthen design culture and perception across the business. Through comprehensive research, they have built five levels that span from companies that use design to create screens to companies that see designers setting the vision of the whole business. That’s where we want to get, and that’s what’s best for the business.

You can find a recording of the talk about design maturity level at InVision here.

Each level describes how the design practice looks and what impact designers can make in the organisation. By putting you and your company on this matrix, you can see the steps you need to take to grow your maturity level.

L1 Producers - Designers are concerned with Pixel pushing and only designing screens. They create wireframes, visuals and prototypes, which means they can only contribute to the product's aesthetics.

L2 Connectors - Here, designers start to branch out and connect to other teams through conversations and workshops, nurturing a good level of collaboration that helps contribute to customer satisfaction, not just aesthetics.

L3 Architects - Designers start to get more systematic in their practice by introducing things like design systems, and they work closer to the product to contribute to the vision and strategy. Therefore, they get involved in high-level organisational conversations and can impact revenue.

L4 Scientists - Designers get very scientific about how we make decisions, and there’s a lot of testing and learning involved in the day-to-day practice. Data becomes vital to guide decisions and unlock key business benefits.

L5 Visionaries - Designers drive business strategy and look into the future, setting the pace for company direction.

Stepping stone

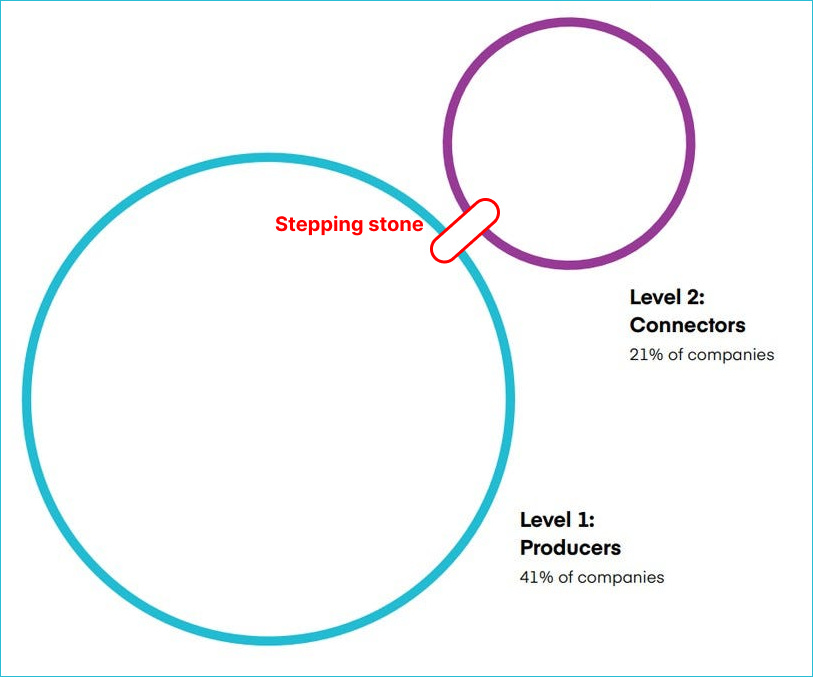

In many of my jobs, agency and in-house, I started from a producer level. I have noticed a middle level between the so-called ‘Producer’ and ‘Connector’ when designers go from simply designing screens to caring about usability.

At this stage, designers run or get involved in usability testing, measuring their designs against users’ needs, goals and pain points. This is a crucial step when designers show the importance of users, bringing them fully into the design process and decision-making, and they can start growing maturity to the next level.

Measuring focus and impact

Whatever the level, there are two main things I find particularly useful when it comes to describing a company's design maturity. It’s the design focus and impact.

The focus is what designers do on a day-to-day.

This goes from being constantly in Figma pushing pixels to other activities focusing more on users’ needs and goals. They start conducting usability testing, then participating in generative research, expanding to running workshops, and participating in C-Level meetings to shape the company strategy.

The impact is what designers influence.

This usually starts with measuring the design effectiveness and usability, growing towards impacting the customer experience, then business profitability, expanding to revenue and the shape and culture of the entire business.

So, think about what you do daily and where your impact is visible. Once you know that, you can start planning to change focus and impact.

Putting the foundation in place for customer-centricity

So, if you find yourself in a company that doesn’t understand customer centricity, looking at a design maturity model can help you plan the work you need to do to take your company closer to your customers and build a more customer-centric business - or at least a better design practice to start with. But changes do not happen overnight, or at least it never happened to me that way. It takes time. But, when you know what is missing in your design practice and understand the business goals, you can create a plan to introduce key design activities to help your business grow and mature your design practice.