When discussing user experience, the focus often revolves around enhancing the experience for end-users—those who interact with consumer-facing applications for shopping, entertainment, or social media. The team’s goals typically aim to reduce the number of individuals who abandon the checkout process, minimise the time it takes to reach the next weekly streak with a silly owl or increase the number of views on reels to maximise ad exposure.

However, there are not only B2C companies in the market. A significant percentage of companies focus on selling products and services to other businesses, and their challenges are completely different. They are less concerned with engagement or click-through rates and more interested in efficiency, cost savings, and other complex objectives that may vary from company to company.

The success metrics for B2C companies can be pretty easy to identify. If companies sell directly to the people using the applications, metrics are all about direct sales. If their business model is ad-driven, like most entertainment apps, metrics are all about engagement, as the more ads users see, the more money the companies make.

Applications for businesses are more complex by nature. They attempt to solve problems in workplaces, sometimes with niche requirements and with a multitude of users. The complexity starts even with the sales cycles, usually long-term and involving large teams. A peculiar difference between a B2B and a B2C application is that the people buying the product aren’t the same people using it. Buyers are trying to solve business problems at the best price possible, and the success metrics are focused on ROI (return on investment), which is more complex to demonstrate. The people using the application aren’t always considered in the buying process because it’s all about the business and the problems to solve.

This complexity changes how products are built and historically has resulted in design being neglected because it is not seen as a contributor to ROI. If the consumer doesn’t understand the design, it’s not a revenue problem, so we don’t need to waste time improving it. If we look at most of the B2B applications on the market, it’s clear that this statement is close to the truth.

Business software is often still in the dark age of design. The reality is that B2B software isn’t as easy to design as a tweet or a video library interface. They are feature-rich applications, often integrated with many other applications and part of a highly complex ecosystem. A simple re-design isn’t all that is needed to boost usage, but what’s required is a more system-level thinking approach that relies heavily on understanding the whole architecture.

The supply chain

I work in a very complex B2B industry: the supply chain. This is a perfect example of an intricate ecosystem, and when you look into a retailer's back office, you can definitely find some outdated interfaces. Most of the design effort is on the website, the customer app, and loyalty programmes. Any of the applications used by staff hangs by a thread with a user experience that resembles MS-DOS (if you are too young to know what that is, simply think about a screen made up of lines of code).

Who is thinking about those applications? Who is designing them and ensuring they provide a seamless experience to staff?

I have worked for years in a startup that aims to solve the problem of returns for retailers to make them more sustainable, efficient, and profitable. Returns are only a tiny part of the supply chain, and even that is incredibly complex. Data rich, loads of touch points and endless integrations.

Let me introduce you to the world of e-commerce returns. We all know it, but at the same time, we don’t. Currently, we order way more stuff than we need, and we have been educated that if we don’t like something, we can just return it. Yes, it has been an undeniably fantastic model for online shopping because it has helped loads of brands grow their online sales and made people more comfortable about shopping online.

However, the pandemic has caused many problems in our society, one of which is related to shopping. When we order more online and return more items, we enter into a vicious cycle that doesn’t benefit anyone. Companies lose money for every return, customers are unsatisfied with the purchase experience, and the planet suffers because the items we return might not all be resalable and, therefore, end up in landfills.

That’s why it’s a big enough problem that needs to be solved. Whilst we can reduce the number of returns, there’s also something that we can do to make them more efficient and sustainable.

One way to solve this problem is to ensure the return is as fast as possible so that items can be restocked and sold again. Several aspects of the return experience can be improved, from where you drop off your parcel to how it is handled when it arrives in stores and warehouses. This means understanding what happens in these places, what staff is asked to do, where the parcels go, and the necessary steps to provide the right level of information to customers and retailers.

But realistically, how many people know what happens in these places? Before looking into the returns problem, I barely knew that all organisations worked to get parcels from A to B! We are often unaware of how things end up in our homes, and I was, too.

Can I solve the efficiency problem of stores or warehouses if I have never been to one? You cannot simply ask AI to solve this. I have tried, and you can get some pretty good guesses about what happens to parcels, but this is when nuances are essential and can make or break a product.

How do you manage this at scale when you work internationally across multiple geographies, from the US to Australia, Japan, Vietnam, the UK, and the rest of Europe?

The only way to better understand staff challenges is to be with them and observe how they work. I have tried field studies, which have helped me get close to understanding the problem.

Field studies

One of the most valuable things about conducting field studies is seeing people in the real world and the environment where they use your application. It’s not like a sterile fictitious lab, but it’s the real deal with its messiness and full of unexpected. The weird scenarios and problems are the ones that you wouldn’t be able to come up with in a million years, but are the ones you want to see because they help you create a product that can deal with real challenges.

Here, I want to share a few of my learnings, which I hope might inspire people or make you think.

What people say is not what people do

I quickly realised that what people say about a product or the overall task completion experience isn’t always accurate or honest. This happens simply because we forget many things we do when using technology. We often get used to a bad interface and memorise the odd shortcuts and ways around it that we have built in our brains.

Therefore, the best approach is to shadow someone, observe what they do, and ask why they do what they do.

I designed an application for warehouse employees from scratch to help them evaluate the correct destination of the items returned by customers. Typically, items in good condition can be restocked, but each item needs to be thoroughly inspected. They often require ironing, refolding, brushing, or other actions to ensure they are ready for the next customer. If an item is unsuitable for restocking, employees must evaluate whether it can be sold to wholesalers or repaired. There are many choices to make, all under the pressure of getting through as many returns as possible.

The employees stand at a desk all day, going through returned parcels, unpacking them, checking the products to ensure they are in good condition, and repackaging them.

I talked to many employees to learn more about their jobs and how they perceive the tasks and gather feedback on the technology involved in the operations. The people I talked to never thought anything was wrong with their application. It did what it needed to do. But it was clear that they didn’t know anything different, and at the end of the day, even if it could be nicer, there were no major pain points.

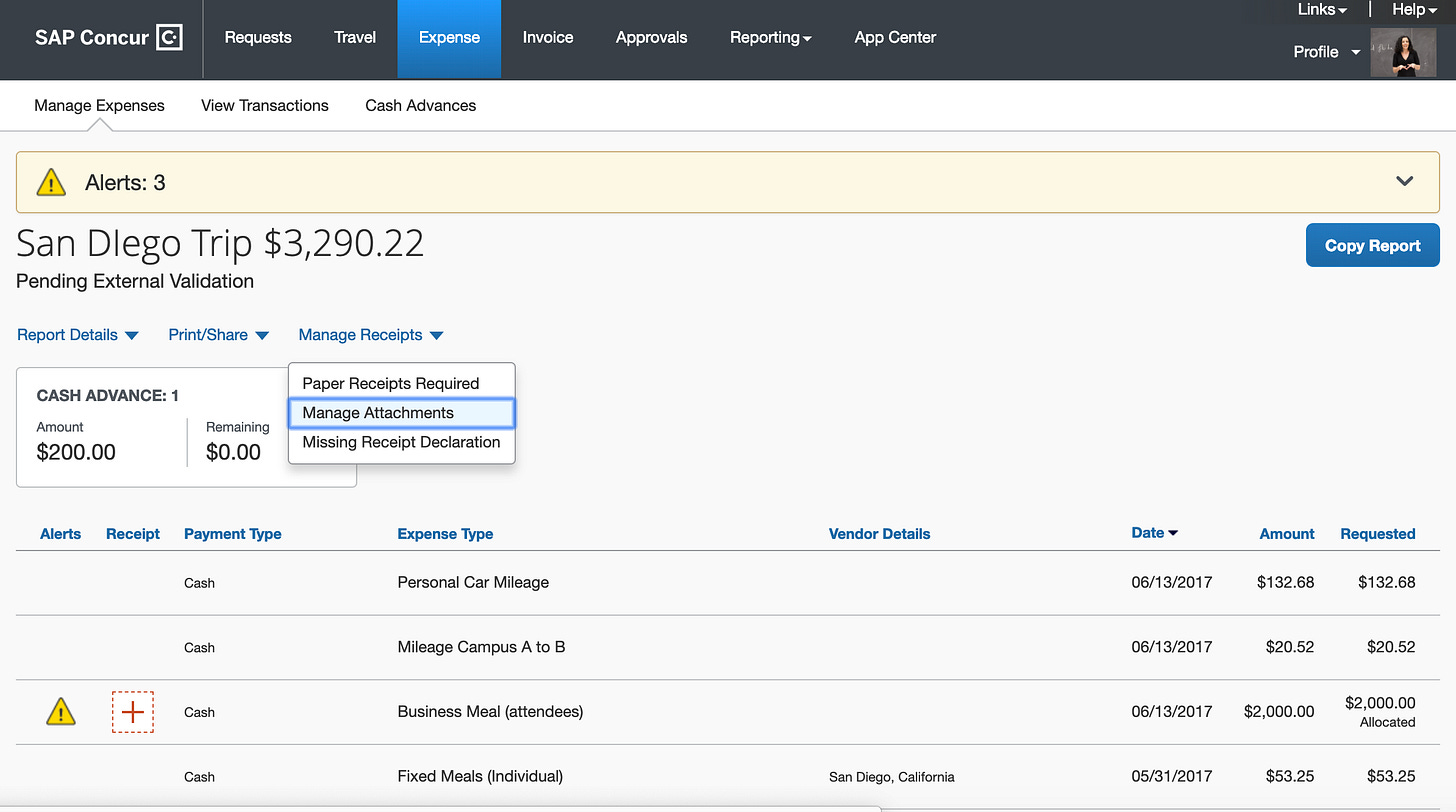

However, observing them, I noticed that the application was essentially a glorified spreadsheet. There was nothing wrong with that, except that each employee had to click on each cell to add a value through a scanner. Also, the application didn’t provide them with all the information they needed to complete the evaluation, and often, they had to switch to another application on the screen to check the item details. It worked, sure, but it was cumbersome and time-consuming.

If we only believe what people say, we will miss many details that could help us evaluate processes.

Stakeholders do not know it all

When creating a new product for staff, we do not have an easy reference point from which to make decisions. Therefore, we tend to rely heavily on the stakeholders' knowledge. This leads to massive bias because stakeholders are driven by metrics provided by someone above. That’s why we are asked to examine the process and create applications.

However, even if knowledgeable about the processes, stakeholders are often removed from the day-to-day activities. This is a huge problem when making important decisions on how the app functions, what should be prioritised and how things should behave or even look.

When I created a mobile app to sort parcels in a warehouse, I worked closely with a small group of stakeholders. They were tasked to develop an app that helped to sort returned parcels by the retailer before they could be dispatched. This was an MVP, but ensuring the parcels were very precisely sorted was essential, as any error would have lost money and especially trust from the first retailers onboarded. So, the stakeholders were highly focused on sorting accuracy, which became an essential metric for the MVP.

When designing the app, we created a detailed process with many confirmation steps for each user's task. This helped ensure that the user knew what they were doing and confirmed that through the app. However, the app became quite convoluted with loads of steps, and from a design perspective, I started to feel uncomfortable with some flows. So, I pushed hard to get a prototype together and went into a warehouse to simulate the process with workers.

The insights we gained in the warehouse were a revelation for everyone who worked on that project - especially the stakeholders. We noticed that the sorting process was generally easy, we didn’t ask a lot from warehouse employees. This meant that once the employee got used to the app, after sorting three or four items, they didn’t read anymore. Employees wanted to go faster, but the app prevented them because of many confirmation checkpoints. This achieved our goal to slow people down and ensure they were making the proper steps. However, this situation generated significant frustration, as employees were still not engaging with the information displayed on the screen.

The stakeholders observing this behaviour reevaluated the initial project metrics. While we aimed to ensure the accuracy of the process, it was equally important to prioritise speed for staff satisfaction, maintain engagement, and ultimately deliver accurate results.

Speed became the primary metric for our staff sorting application, with accuracy considered a secondary factor. By observing how staff interacted with the application and handled parcels, we generated new ideas to enhance accuracy.

This shift allowed us to rethink the main workflows within the application and develop various strategies to ensure staff were aware of the correct sorting options. We decided to introduce sound feedback to provide clear notifications and enable the application to handle most accuracy checks, alleviating that burden from the staff.

New country, new language, new challenges

Each country has developed a unique approach to managing the supply chain. While the fundamentals remain the same—businesses moving parcels from point A to point B—how people shop online and receive their parcels can differ significantly. I learned this while working in countries like Japan and Vietnam.

For instance, in Japan, small shops are equipped with all the latest technology. Each shop has kiosks, printers, and other devices that allow you to perform various tasks yourself. However, the staff receives a sticker from the courier to confirm that a shipment has been completed. Yes, a sticker, like the kind you can put on your laptop! At the end of the week, they can tally the stickers to determine how many shipments were made. It's wild!

In Vietnam, e-commerce is relatively new compared to Europe or the USA, but you can purchase almost anything online. What's fascinating is that you can pay in cash when the courier arrives at your door—this is known as cash-on-delivery. You can also ask the courier to wait while you try on your items, and you can return them on the spot if you’re not satisfied. Talking about fast returns, this method definitely achieves that.

When exploring ways to make returns more efficient in such countries, there’s no other way than to pack your bag and see how the world works with your own eyes. Field study again wins over any other type of research, but there are a few mistakes that you might want to avoid.

Conducting field studies in a country where you do not speak the language can be challenging, as I learned while working in Vietnam. Our business employed an interpreter to assist us in collaborating with our partners and exploring warehouses, shops, and post offices as we observed workers and interviewed them.

I quickly learned that translation is a complex skill. Although I have some understanding of this, as English is my second language, it became even more apparent when we needed to discuss intricate topics related to delivery and returns, including specific processes, digital screens, and delivery notes. I assumed that anyone who spoke both languages could effectively facilitate the communication. Unfortunately, that assumption was so flawed. The specifics of our subject matter posed a barrier, and the interpreter struggled to convey specific processes accurately in English.

On another occasion, we had a different interpreter, and we thought it wouldn’t be an issue—after all, one interpreter should be as good as another. However, this was another flawed assumption. The new interpreter did not translate the processes in detail or at all! Instead, she seemed to add her interpretations to everything she heard or decide that something wasn’t relevant. She genuinely thought she was helping us, but we couldn’t gather honest feedback or formulate the right follow-up questions, leaving us with significant information gaps.

I strongly recommend thoroughly interviewing interpreters rather than using agencies that provide whoever is available. Finding someone with a solid understanding of the subject matter is essential to ensuring clear and accurate communication. I would even say that you need a researcher, not an interpreter, someone who understands the insights you expect from such a research trip.

The space is key

Field studies offer a rather brilliant opportunity to observe the actual environment where your application will be used. With consumer apps, we can make reasonable assumptions about usage contexts—picture someone using Duolingo or Netflix whilst relaxing at home or on their morning commute, likely ‘double-screening’. However, the context becomes far more nuanced when it comes to warehouse applications. What's the physical environment like? How do staff navigate the space? What's their workflow? These crucial details only became clear once we conducted proper field observations.

During our involvement in various commercial discussions (which is somewhat unconventional for a design team, but that's a story for another article), we identified a clear need for sorting and grading returns. While our clients had their logistics covered with warehouses and courier services, they lacked the appropriate technology to assess returned items and determine their next destination.

As per any designed book, we started with the double diamond and did some discovery. Joking, of course not! We didn’t have time or budget for that, so we went straight to Figma. We were rather optimistic (or delusional) considering our predominantly web-based experience, but we kept pushing stakeholders to observe existing warehouses. Our persistence paid dividends when we finally gained access to several warehouses, providing invaluable insights into their returns operations—worth far more than any number of design iterations in isolation.

The scale rather took us aback. These facilities are properly enormous—it takes a good fifteen minutes to walk from one end to the other. We observed staff at their workstations, surrounded by an impressive array of tools: scissors, tape, bags, printers, scanners, and various supplies, all whilst managing parcels and navigating between storage areas. Most revealing was their reliance on keyboard shortcuts rather than mice—a crucial insight that fundamentally shifted our interface design approach. The staff had even developed clever workarounds, printing custom QR codes and barcodes for frequently used functions. Every aspect was carefully optimised for their environment and efficiency.

Perhaps most enlightening was a rather fundamental oversight we discovered while walking about with our mobile phones: connectivity. Reliable WiFi isn't a given in these vast spaces. How does one design a data-intensive application for such an environment? Fortunately, we'd had the foresight to bring our development team along. Their firsthand experience of these constraints proved essential in architecting an infrastructure suited to these rather challenging conditions.

Go out of the building

I feel lucky as a designer to have had the opportunity to do so many on-site visits and gather insights in context. Also, it’s priceless to see so many people using a product you helped create.

If you work for an enterprise company, push to get more field studies done. The level of insight justifies any cost. Field studies are invaluable because they provide deep insights into user behaviour that cannot be captured through traditional methods alone. By observing users in their natural work environments, we can develop solutions that truly meet user needs and improve overall system efficiency. Enhancing the user experience for workers not only boosts their productivity but also indirectly enhances customer satisfaction by ensuring seamless operations.

- Cultural Nuances: Cultural differences significantly influenced application use across different regions. For example, certain intuitive interface elements in one culture were confusing in another, requiring localised design adaptations.

- Efficiency Improvements: By addressing the pain points identified during field studies, design teams implemented changes that improved workflow efficiency and reduced errors. This had a positive ripple effect on end-user satisfaction by ensuring smoother operations.

- Space! You can see the space around people, and this helps you evaluate how the application and the processes need to be designed